Overcoming Atomic Anxiety in the Land of the Rising Sun

Author: MATT COTÉ // Images: REUBEN KRABBE

Shared on the RSIC website with the permission of the author

IN 1942, UNDERNEATH STAGG FIELD at the University of Chicago, Enrico Fermi fired up the world’s first nuclear reactor. It used 50 tons of radioactive material to produce a steady flow of one half-watt of power per hour. As the technology advanced over the next 76 years, 31 countries would come to use it to produce massive amounts of electricity. Even Japan, ravaged by two atomic bombs in 1945, embraced the power of the atom.

Then, in 2011, an earthquake and tsunami rocked that country’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, creating the world’s second-ever level-seven nuclear disaster, after the 1986 Chernobyl meltdown in the former U.S.S.R. News outlets across the globe evoked the end of the world anew as hysteria mounted. Seven short years later, I slide off a ski lift in Hakuba, Japan, with record numbers of other snow seekers looking to imbibe in the Pacific nation’s unparalleled bounty of early February powder. No more apocalyptic headlines, no more endtimes rhetoric, just epic skiing on the brain. Insane amounts of estern skiers are now swarming an island nation that, a short time ago, was thought by many would bring about the beginning of the end. But as attention spans shift from offending isotopes to a modern explosion of Japanese powder, what happened with Fukushima, and is the skiing safe?

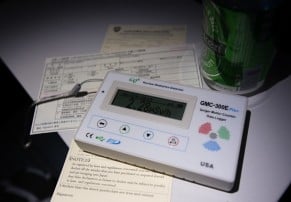

I HAD RESERVATIONS about coming to Japan. My travel insurance even had a clause excluding coverage or radiation poisoning. In between mind-blowing deep laps at the tree-skiing paradise of Cortina Ski Resort, fellow Canadian ski voyageurs Reuben Krabbe, Adam McCraw and Carter McMillan join me in monitoring a small white device not much bigger than a smartphone. My Geiger counter was $140 and measures beta, gamma and X-ray radiation. Every so often, when lucid moments return, I remember to check it. When I do, readings are normal, but Krabbe still mutes the machine’s obnoxious clicking and hides it from local eyes. The nuclear subject is taboo here. Godzilla is just one example of Japan’s complex and uneasy relationship with nuclear energy. Like that beast, the mountains here have created their own mythos. Hakuba lies in the soaring Japanese Alps. Mimicking a European valley, a series of ski areas spans the range, which stands as high as 3,100 metres.

The soft volcanic slopes have eroded into creased, otherworldly shapes over millennia, and easily transfix a Westerner. Equally dazzling are the geothermal currents of water they use to clear the streets, the wild clans of monkeys, the proliferous onsens (Japanese hot springs) and the surreally compact and traditional yet technocratic society buried under metres of snow—where you can get anything you need from a vending machine. Hakuba’s powder season picks up in early December and lasts through mid-February. Cold air rolls off Siberia, picking up moisture from the Pacific, dumping it almost nightly along Japan’s wringing spine. We’re here just a week after the Freeride World Tour, which had to retreat with its tail between its legs due to too much snow.

We, however, are hitting a rare window of full alpine visibility as the sun astonishingly pokes through after each storm and the snow settles each day. McCraw and McMillan instantly chase the most technical lines: steep spines with rolling sloughs and tight airs over glide cracks in the deep snowpack. The Lake Louise, Alberta, natives feel invincible in the infinite cushion around them as they jib trees, backflip rock outcroppings and trace long, knife-edged lines to their terminuses at full pin. “That was the best run of my life,” is a phrase on repeat. Throughout, they don’t stop to think twice about any hidden danger at the atomic level. “It never even crossed my mind before coming,” says McCraw. “This is my second trip, and I didn’t think to worry about it,” adds McMillan. From Americans to Australians, no one else we meet expresses any sense of danger or concern when asked. I seem to be the only skier in the country still traumatized by the idea. Though it’s hard to say how many people fear the same thing, and just don’t visit

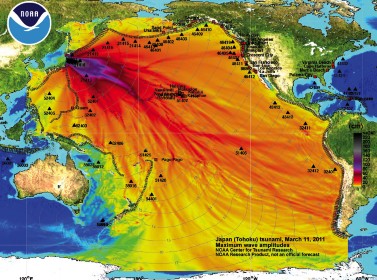

ALL SORTS OF MISINFORMATION hit the airwaves in the aftermath of Fukushima. Most notable was a map showing the purported flow of radioactive discharge across the Pacific in incendiary shades of red. This was actually a wave map from the tsunami, and had nothing to do with radiation. While news media reported that Japanese authorities weren’t able to contain spillage, even the likes of David Suzuki roused global fears. In 2013, he stated, “I have seen a paper which says if in fact the fourth plant [from the same Fukushima facility] goes under in an earthquake and those rods are exposed, it’s bye-bye Japan and everybody on the west coast of North America should evacuate. If that isn’t terrifying, I don’t know what is.” Suzuki later walked those comments back as physicists around the world reprimanded him—things weren’t nearly that dire. A subsequent quake came and went without further complication. But the situation is still not over. When the tsunami knocked out the plant’s cooling systems, a series of explosions and meltdowns followed, sending radiation into the air and dropping nuclear fuels through the facility’s floor and onto the water table. The melted rods still sit there today, contaminating passing groundwater. TEPCO, the utility company responsible for the plant, collects and stores that water daily in giant on-site vats. Just like regular nuclear waste, no one knows what do with it, and it’s simply accumulating. It’s expected to take 30 to 40 years to fully remove the melted-down fuel, which is radioactive enough to kill a human in one minute.

ALL SORTS OF MISINFORMATION hit the airwaves in the aftermath of Fukushima. Most notable was a map showing the purported flow of radioactive discharge across the Pacific in incendiary shades of red. This was actually a wave map from the tsunami, and had nothing to do with radiation. While news media reported that Japanese authorities weren’t able to contain spillage, even the likes of David Suzuki roused global fears. In 2013, he stated, “I have seen a paper which says if in fact the fourth plant [from the same Fukushima facility] goes under in an earthquake and those rods are exposed, it’s bye-bye Japan and everybody on the west coast of North America should evacuate. If that isn’t terrifying, I don’t know what is.” Suzuki later walked those comments back as physicists around the world reprimanded him—things weren’t nearly that dire. A subsequent quake came and went without further complication. But the situation is still not over. When the tsunami knocked out the plant’s cooling systems, a series of explosions and meltdowns followed, sending radiation into the air and dropping nuclear fuels through the facility’s floor and onto the water table. The melted rods still sit there today, contaminating passing groundwater. TEPCO, the utility company responsible for the plant, collects and stores that water daily in giant on-site vats. Just like regular nuclear waste, no one knows what do with it, and it’s simply accumulating. It’s expected to take 30 to 40 years to fully remove the melted-down fuel, which is radioactive enough to kill a human in one minute.

While the Soviet Union abandoned the 1,000-square-kilometre tract of land around Chernobyl, then built a giant shield over the plant, Japan can’t do the same. It’s an archipelago the size of California, with three times the population—127 million. Instead, they’ve implemented an exhaustive cleanup to decontaminate the surrounding area, at a cost of $180 billion. Japan maintains a 20-kilometre exclusion zone around the Fukushima Daiichi Plant, though the U.S. government recommends an 80-kilometre one. But by the summer of 2018, most of the beaches around Fukushima will have reopened. You can even find tour operators that will take tourists to visit the plant via a boat ride that getswithin 1.5 kilometers of it.

THREE-HUNDRED KILOMETRES from Fukushima, we take our own tour of the adjacent backcountry at Tsugaike Ski Resort, sliding conveniently back inbounds at the end of each run. McCraw and McMillan jockey with Swedish tourists and high five lifties as we settle into the mass of caucasian skiers enjoying the country like it was our own. We later learn that Goryu and Mt. Norikura Resorts are ideal for linking up runs between areas, that lift tickets throughout the valley are startlingly affordable, and that they can even be purchased by the run. The Land of the Rising Sun is all about volume. British Columbia has 38 ski areas. Japan, by comparison, with less than half the same land mass, has over 500. Many of them have historically banned skiing in trees, or even out of bounds. But the booming resorts of Hakuba are much more permissive; part of their increased international appeal. The Hakuba Valley Promotion Board says foreign visitors quadrupled from the 2012-13 season to 2017-18, finishing at about 330,400.

The designated backcountry gates from which you can leave the resort boundaries are a huge draw. It’s also spawned a tidy market for Western ski guides like Jasmin Caton of Nelson, B.C., who we steal a few runs with in-between work duties. “I’ve been to Japan twice,” she says. “I think five years ago is when it really started taking off as a place for Canadian guides to run trips for guests. I haven’t run into anyone who’s concerned with Fukushima contamination, and haven’t thought about it myself. When I am on trips, concerns about guests bobbling over in the deep snow and suffocating seem more pressing. But maybe I haven’t looked into it because I don’t really want to know.” Neither does anyone else, it seems. Peter Anderson of Simon Fraser University specializes in disaster communication, and explains this phenomenon,

“There tends to be a window around these major events that attracts a focus… I don’t think that commercial media are interested in trying to monitor something even on a month-by-month basis where the results are negligible.” Anderson, who’s studied the overall risk on the ground in Japan and says it’s complex, adds that the media have no mandate to provide closure. In the absence of it, people’s collective memory can be short, and they become “comfortably numb” when headlines fade. “While it looks like there’s some sort of human, emotional story to be had, the media are all over that, because their job generally is to attract audiences. In this case you had a rapid-onset event into a slow recovery that’s going to go on for years. Within that time-frame, there’s a cutoff point for the media. It’s really hard to get sustained interest.” In other words, Fukushima’s media coverage—past or present, frenzied or absent—has had very little to do with any real danger.

AS THE SUN SOAKS the landscape in its own radiation, we adapt our routine to its whims. We bag early morning high-alpine steeps, and late-day robot-poured beers while scuttling around on piste. McCraw and McMillan send massive spread eagles over cat tracks at HappoOne Winter Resort, the valley’s most sprawling and tallest area, as flocks of Japanese ski students lurch by in matching uniforms while learning to pizza and french fry. The odd patroller catches our two Albertans scoping closed lines, and isn’t shy to warn them to keep in check—which they reluctantly do. From mid-station patios, while the Geiger counter remains reassuringly calm, we watch the sun tear through the solar-dished upper reaches of the range and new snow crumble—just like how radiation affects living cells.

Dr. Curtis B. Caldwell is the chief scientist at the Radiation Safety Institute of Canada, and walks me through it.

“There are particles, and then there are also rays. If we look at the rays, they’re similar to light, just a higher energy. A bunch of light photons can burn your skin, like a sunburn, whereas photons of gamma rays or X-rays can actually interact more deeply in you to cause radiation burns… that’s when you’re in a really high radiation area. If there are low levels of radiation, we’re not concerned about the same thing, about a burn. What can happen is you can damage DNA, and then you can get mutation, and that might induce a cancer.”

“There are particles, and then there are also rays. If we look at the rays, they’re similar to light, just a higher energy. A bunch of light photons can burn your skin, like a sunburn, whereas photons of gamma rays or X-rays can actually interact more deeply in you to cause radiation burns… that’s when you’re in a really high radiation area. If there are low levels of radiation, we’re not concerned about the same thing, about a burn. What can happen is you can damage DNA, and then you can get mutation, and that might induce a cancer.”

Dr. Caldwell is quick to remind me, though, that this still falls within the parametres of overall risk. He says the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba—landlocked in the geographical centre of North America—is naturally five times more radioactive than Tokyo is right now, just from normal cosmic background radiation and minerals in the soil. He says the universe is already a radioactive place. Being high on mountains, and thus shielded by less atmosphere, already gives skiers a higher dose of radiation than anyone at sea level—whether in Canada or Japan. It’s also why pilots have limited hours they’re allowed to fly; the higher the altitude, the more radiation you get. One millisievert of exposure will increase your risk of cancer by one in 20,000. According to current readings confirmed by the independent citizen monitoring group Safecast.org, with its online heatmap, you’re likely to get less than this in a year in most of Japan. But you can get multiple times that amount on a single international flight, or during a CT scan. To boot, the normal North American risk for cancer is already one in five.

“I don’t think [radiation is] the major risk in skiing,” Caldwell says, “and the benefits probably outweigh the risk. Japan is rightly very sensitive to radiation because they’re the only people who’ve had an atomic bomb dropped on them. But in Japan itself, other than right in the immediate area of Fukushima, there’s in fact no increase in background levels of radiation. Everybody seems to remember Fukushima as this terrible radioactive event. Fukushima wasn’t a terrible radioactive event, it was a terrible tsunami that killed 20,000 people. Radiation killed zero people.”

“I don’t think [radiation is] the major risk in skiing,” Caldwell says, “and the benefits probably outweigh the risk. Japan is rightly very sensitive to radiation because they’re the only people who’ve had an atomic bomb dropped on them. But in Japan itself, other than right in the immediate area of Fukushima, there’s in fact no increase in background levels of radiation. Everybody seems to remember Fukushima as this terrible radioactive event. Fukushima wasn’t a terrible radioactive event, it was a terrible tsunami that killed 20,000 people. Radiation killed zero people.”

EACH NIGHT, we find a new favourite restaurant. Ramen, Korean barbeque or Japanese curry—it’s all mind-bendingly delicious. While McCraw and McMillan struggle to sit cross-legged (not quite old enough to have adopted yoga yet), Krabbe and I delight that there’s not been so much as a chirp from my Geiger counter in two weeks of ordering seafood. Whatever Japanese authority is responsible for vetting food, at this point in time, seems be dialled. At least in Hakuba. Given the direction of ocean currents, though, some worry we’re actually more exposed to Fukushima radiation on B.C.’s west coast than here on the west coast of Japan. In 2015, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution reported detecting radioactive Fukushima isotopes in Ucluelet, a fishing and surfing town on Vancouver Island. The cesium-137 they found, however, produced radiation levels 2,000 times lower than what Health Canada allows in normal drinking water.

There’s also a B.C. citizen-based ocean monitoring group called Fukushima in FORM with 60 stations along the province’s southern coast. According to it, most of the Fukushima radiation remains in a plume1,000 kilometres offshore, and none of it comes close to approaching a concerning level. It’s about 1,000 times lower than one millisievert, our yearly allowance for X-rays. Given the plume’s half-life (radiation’s rate of decay), the contamination is expected to be basically gone by 2021. Conversely, the contamination from atomic-bombs testing in the ’50s and ’60s is, today, still 100 times greater than Fukushima’s. On any remaining hysteria or health fanaticism, like my own, Anderson says, “When you’re dealing with technical matters—types of hazard that require extensive research, monitoring and interpretation of huge amounts of data that are also accompanied by uncertainty—I think that’s something that’s hard for the media to get their heads around. Especially if we’re looking at a long duration event [like the Fukushima recovery].”

IT MAY BE A HAPPY ACCIDENT that our presumption of “no news is good news” actually turns out to be correct this time around, but it’s one I’ll happily indulge in. Like Dr. Caldwell says, we evolved in a nuclear world, and, for now, are still thriving in it. Skiers in Japan more than most. As our delirious team makes its last magical turns down Cortina Resort’s jungly contours, we eventually merge into a tight, snaking valley carved like a luge-track with side hits. We air off every feature in train formation, squeezing the most from our last moments on Japanese slopes. We pass an old steel and concrete dam covered in scratch marks from past playful skiers who’ve jibbed it. McCraw and McMillan add their own signatures, tail tapping and landing switch while bubbling over with laughter. If this time in Japan has been about anything, it’s been about managing uncertainty. At this point, the only thing we know for sure is we’ll be back.

HIGH FIVES from the author to:

Hakuba Valley Promotion Board – hakubavalley.com

Hakuba Powder Lodging – hakubapowderlodging.com

Blizzard Skis – blizzardsports.com